Environmental management, reimagined

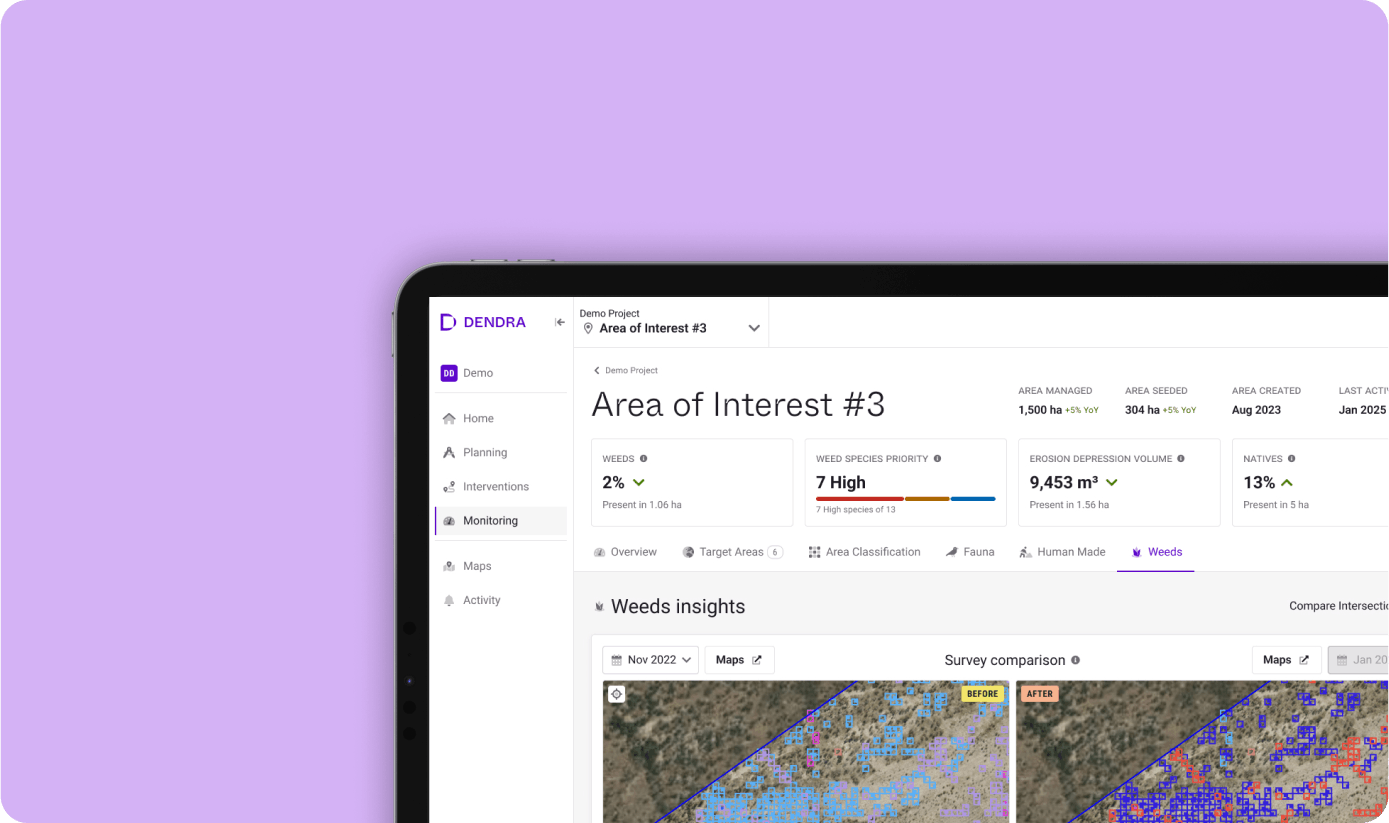

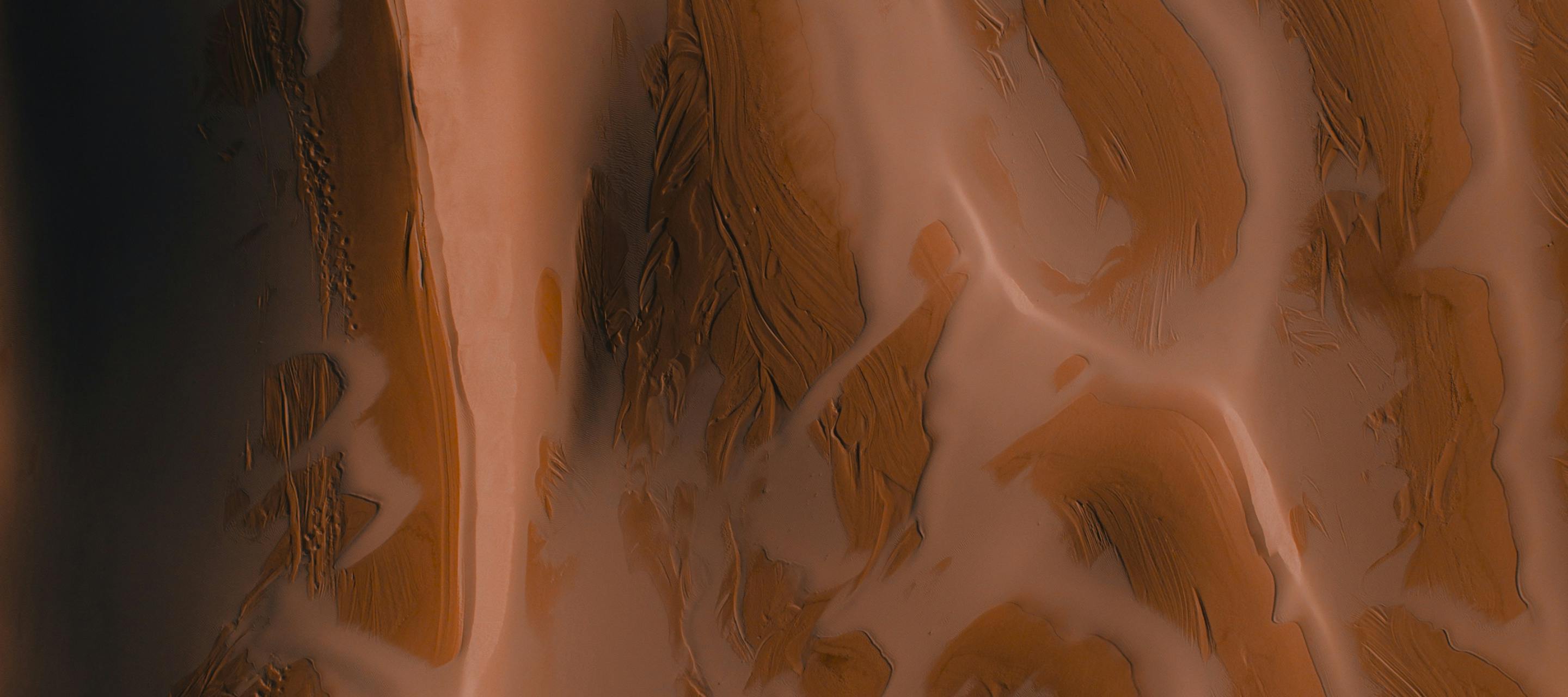

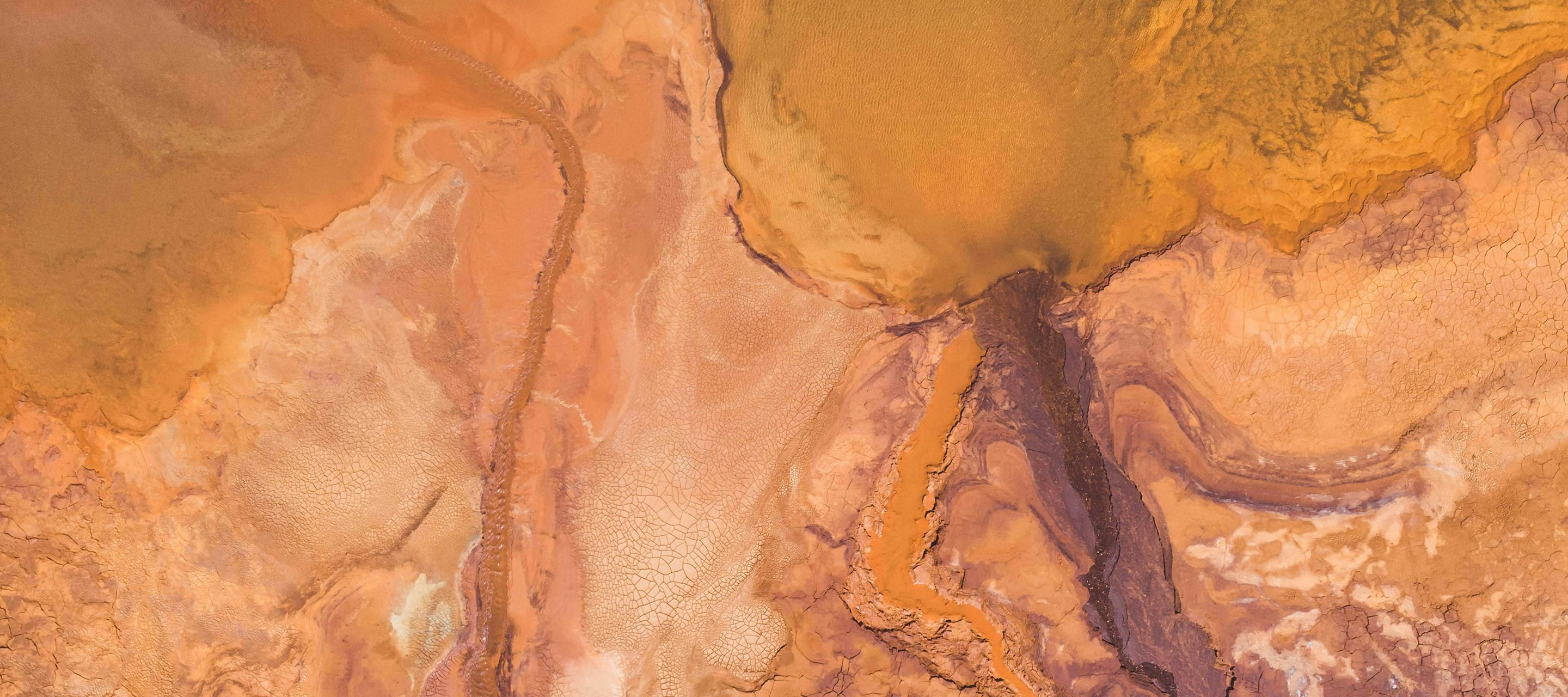

Transform how you monitor, protect and restore large-scale ecosystems with the Dendra Platform. Use ultra-high-resolution maps and AI-powered insights to inform incisive interventions every step of the way.

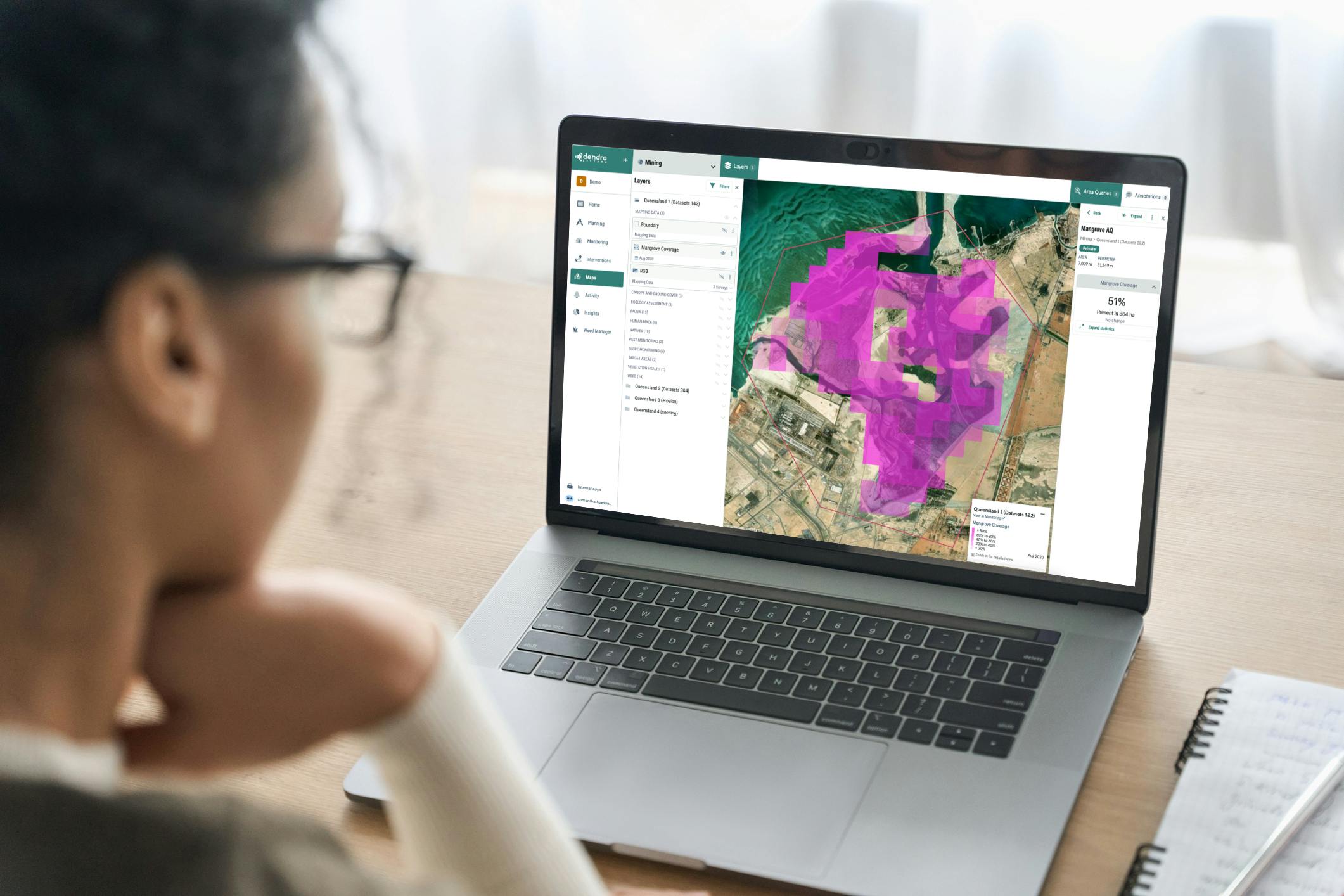

Bring clarity to the complexity of environmental management with Dendra’s Optical Intelligence.

At Dendra, we’re revolutionising environmental management through our game-changing platform, helping you to manage and restore natural environments like never before.

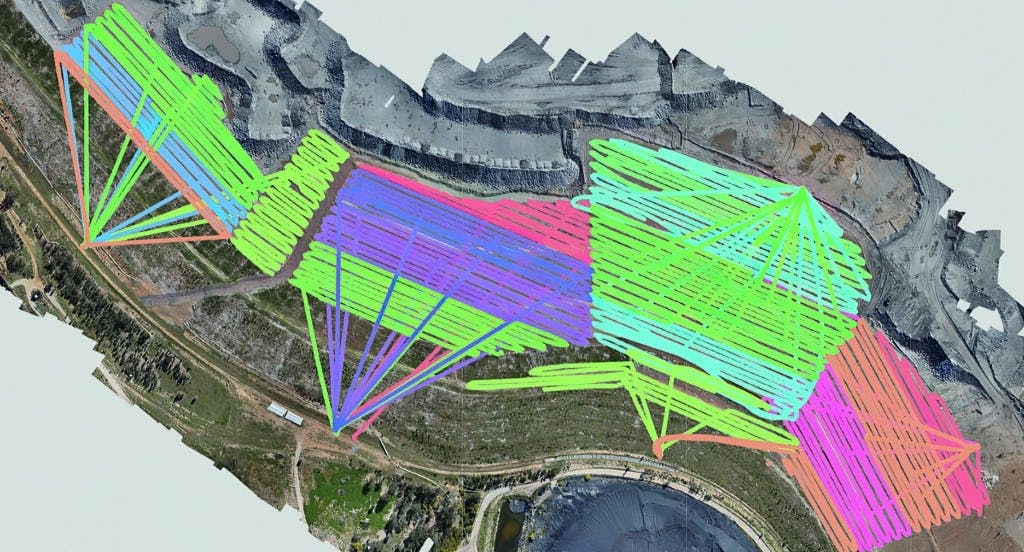

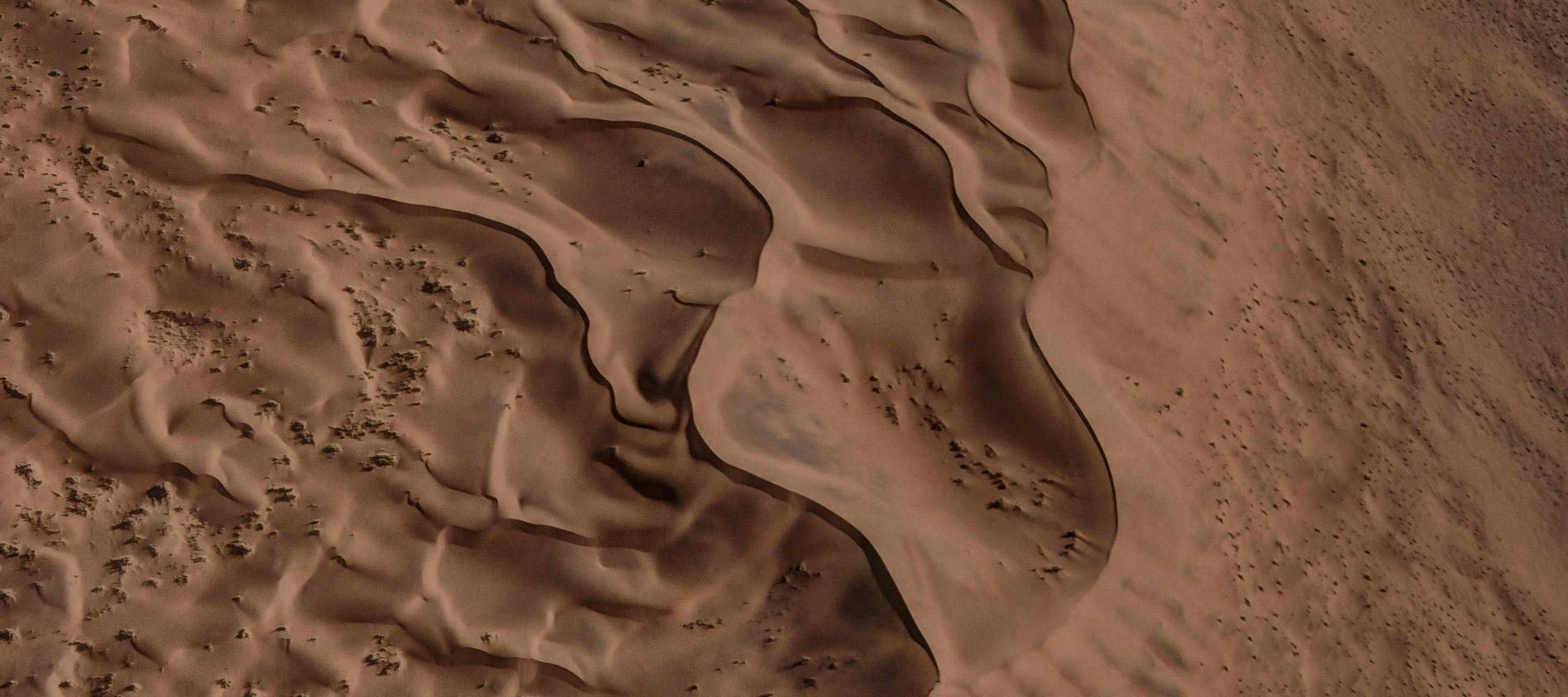

Perform digital flyovers of your entire site, with each pixel showing an area as small as 5.6mm.

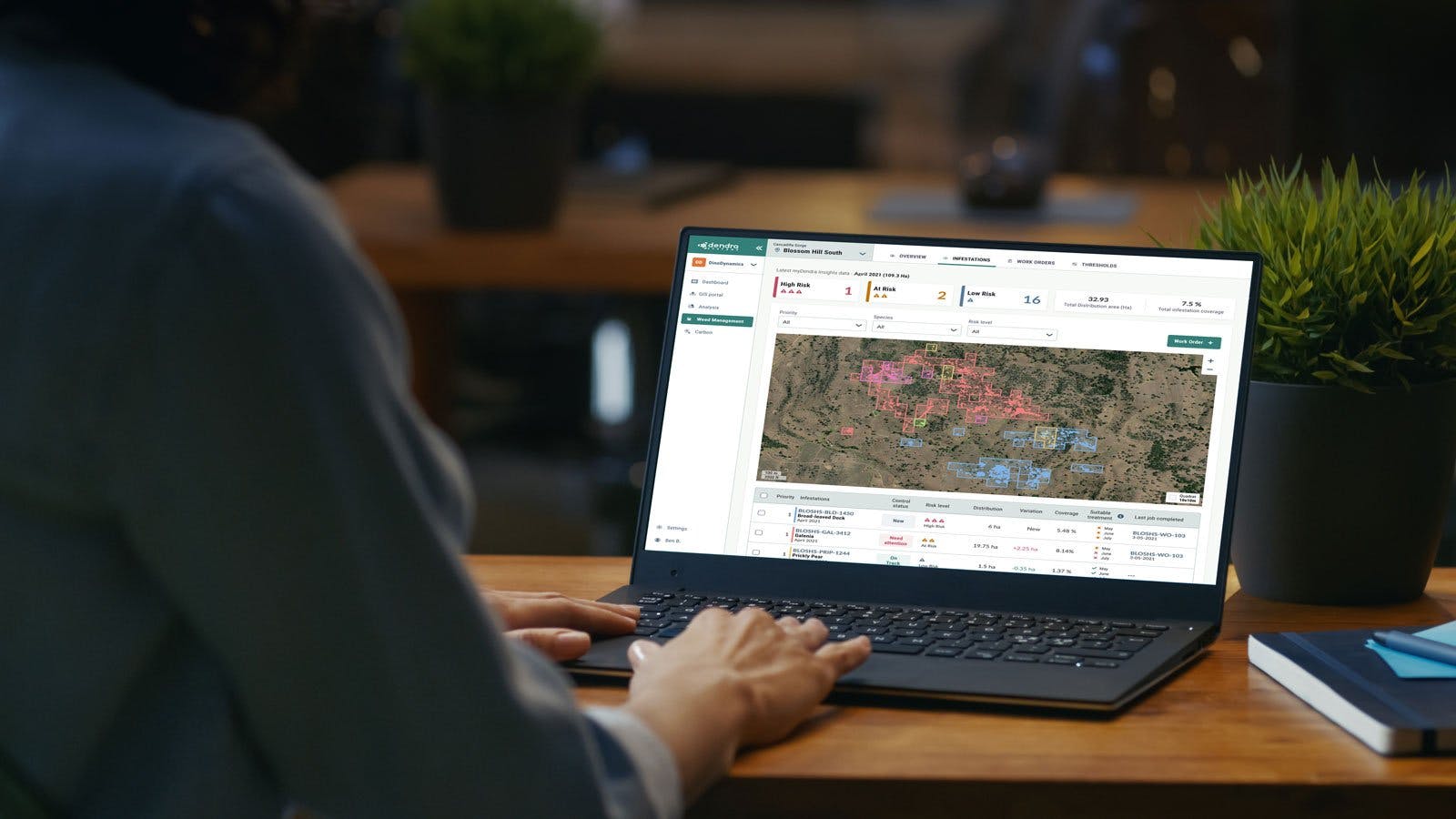

Use ecology-trained AI to identify species, erosion features, man-made objects and more.

Unify your plans in one place, ensuring transparency and cooperation between stakeholders.

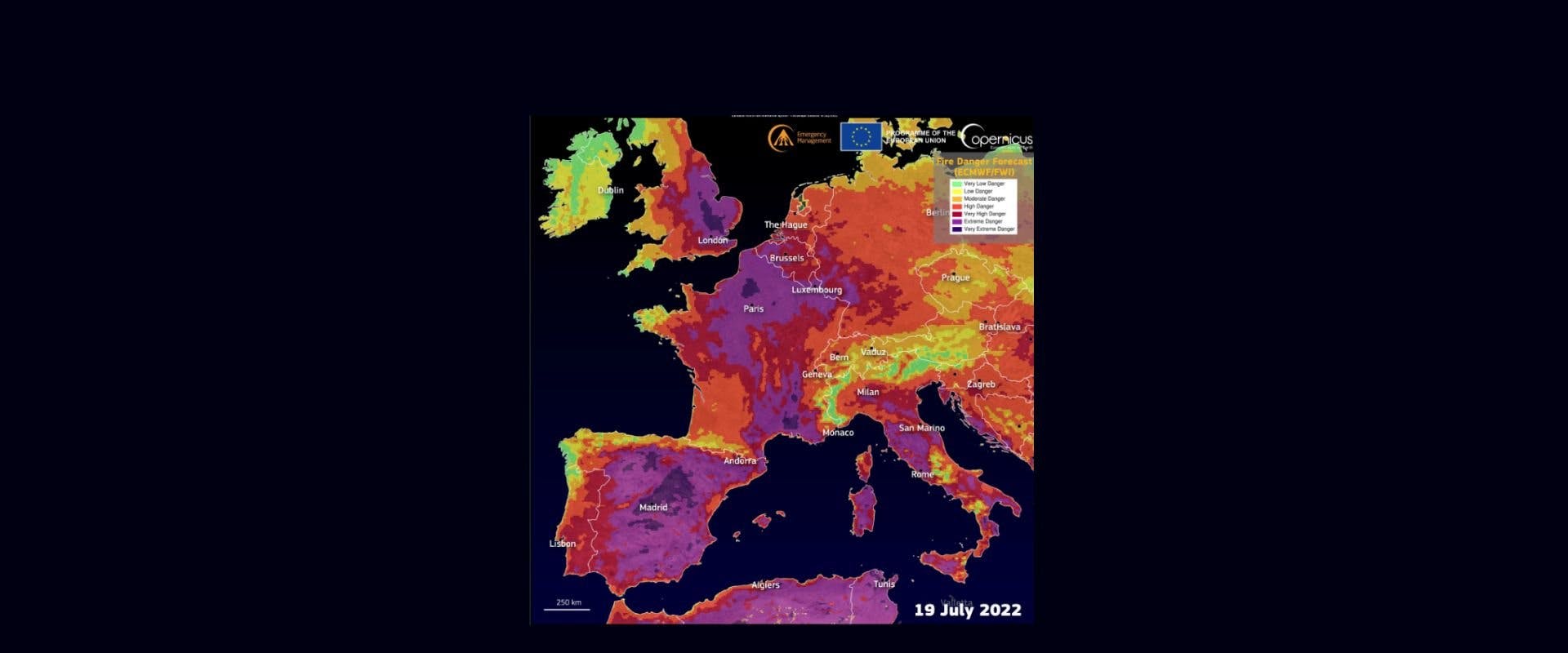

Focus on the most important trends by instantly identifying changes between surveys.

Make quicker, better informed decisions, based on a multi-layered picture of your ecosystem

Operate more efficiently and effectively with fast AI analysis.

Dendra for

Environmental management, elevated. Access ultra-high-resolution maps and AI-powered insights with a platform designed for the whole restoration lifecycle.

Notable Customers

We’re extremely grateful to our customers, who share our passion for bringing innovation to environmental management.

See it in action.

Explore our video library of feature demos and explainers to see the power of the Dendra Platform in action.